Tests as cultural artifacts

As with any other product of human activity, tests are cultural artifacts (Solano-Flores, 2011, p. 3) existing within a given worldview. As such, elements of the instrument-development process are prescribed necessarily by the cultural worldview under which they are presented. The cultural validity of tests is the degree to which they address sociocultural influences such as values, beliefs, experiences, and epistemologies inherent within cultures as well as the socioeconomic conditions under which cultural groups exist (Solano-Flores & Nelson-Barber, 2001). Assessments function as operational projections of one part of a theoretical-knowledge space. Educational instrument developers seek a formal structure that maintains alignment both within and between the conceptual knowledge space elements and the operational elements of an instrument. From a broad perspective, educational instrument developers also seek a formal structure that maintains alignment to such elements as the constructs of knowledge, learning expectations, the educational framework, adopted curriculum , methods of instruction, and forms of assessment.

An instrument-development process is comprised of an array of conceptual and operational components and is advanced through thoughtful consideration and decision-making. In the case where assessment instruments are developed within Western worldviews and applied within an Indigenous world view, since each element, consideration, and decision is influenced by the worldview in which it exists, a multitude of opportunities exist for misalignment between the two worldviews. This led to the posing of three fundamental questions about this form of misalignment that exists within instrument-development processes: What do we call this? Why is this a problem? What do we do about it?

What do we call this?

Measurement validity refers to the degree to which evidence and theory support the interpretations of test scores for proposed uses of tests (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education, 2014). Key elements of this definition are addressed by the terms “evidence,” “theory,” “interpretations,” “scores,” “uses,” and “tests.” The meaning of these terms within the very definition of measurement validity is grounded in and influenced by the worldview under which the instrument development occurs.

Misalignment that is grounded in cultural and linguistic differences has been referred to as “disjuncture” (Appadurai, 1996; Meek, 2010; Wyman et al., 2010) or “discontinuity” (Bougie, Wright, & Taylor, 2003; Brown-Jeffy & Cooper, 2011; Edwards, 2006; Meek, 2007). Cultural discontinuity in school settings has been defined conceptually as “a school-based behavioral process where the cultural value-based learning preferences and practices of many ethnic minority students—those typically originating from home or parental socialization activities— are discontinued at school” (Tyler et al., 2008). The cultural-discontinuity hypothesis posits that culturally-based differences in the communication styles of minority students’ home and the Anglo culture of the school lead to conflicts, misunderstandings, and, ultimately, failure for those students (Ledlow, 1992). Cultural discontinuity arises for students when their personal values clash with the ideals that shape their school system (Wiesner, 2006). Ladson-Billings (1995) described the “discontinuity” problem as the gap between what students experience at home and what they experience at school with respect to their interactions of speech and language with teachers.

Measurement disjuncture is defined here as the misalignment that occurs when elements of an instrument-development process from one worldview are applied to the instrument- development process of another worldview. Although measurement disjunctures can occur across worldviews, environments or settings, this research will center on the measurement disjuncture that exists across Western and Indigenous worldviews.

Why is this a problem?

When assessment instruments are developed within a Western worldview and are applied within an Indigenous setting, measurement disjuncture results. Measurement disjuncture affects the establishment of measurement validity, and, hence, the inferences made based on the scores derived from such assessments. This is primarily due to the introduction of measurement error caused by the misalignment.

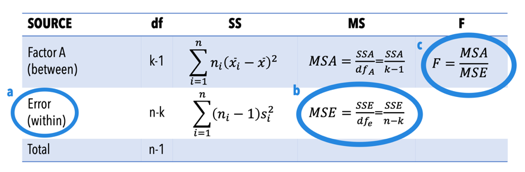

In addition to affecting interpretations based on assessment results, measurement error introduced by measurement disjuncture negatively affects the conclusions drawn from quantitative research designs. The figure below presents a typical analysis of variance (ANOVA) table used to interpret the differences between groups in a controlled quantitative study. Three elements of the table that are influenced by measurement disjuncture are noted. In reference to the figure below, when the error term (a) increases, the mean square error (b) increases causing the value of the F statistic (c) to decrease. With a smaller than expected F statistic, researchers are less likely to acknowledge that the treatment has had an effect when, in fact, it has, which represents a Type II error.

When measurement disjuncture exists within assessment instruments used by educational researchers, the influence of interventions may end up being undervalued. In practical terms, researchers evaluating programs to improve educational outcomes for Indigenous people through the application of assessment instruments developed within a Western worldview may end up undervaluing the influence of such programs.

What do we do about it?

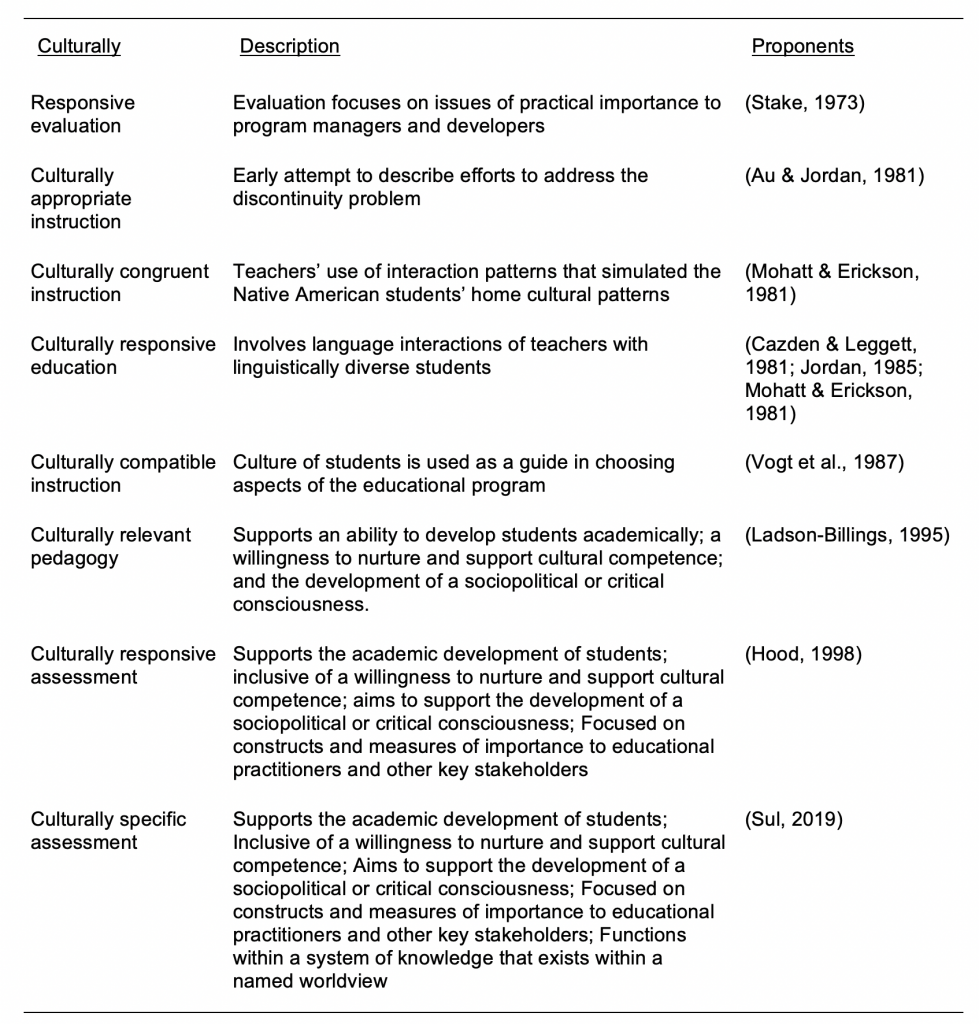

Although the term measurement disjuncture is presented here, attempts to both describe and address the disjuncture within broader educational environments are not new. Au and Jordan (1981) described as “culturally appropriate” the incorporation of “talk story” into a program of reading instruction for Native Hawaiian students that improved upon expected scores on standardized reading tests. Mohatt, Erickson, Trueba, and Guthrie (1981) used the term “culturally congruent” to describe teachers’ use of interaction patterns that simulated Native American students’ home cultural patterns to produce improved academic performance. Jordan (1985) defined educational practices as “culturally compatible” when the culture of students is used as a guide in choosing aspects of the educational program to maximize academically desired behaviors and minimize undesired behaviors. Researchers beginning in the 1980s used the term “culturally responsive education” to describe the language interactions of teachers with linguistically diverse and Native American students (Cazden & Leggett, 1981; Erickson & Mohatt, 1982). Erickson and Mohatt (1982) suggested their notion of culturally responsive teaching could be seen as a beginning step for bridging the gap between home and school. Ladson-Billings (1995) claimed the term culturally responsive represented a more expansive, dynamic, and synergistic relationship between the culture of the school and that of the home and greater community.

Culturally Specific Assessment

Drawing upon the lineage of research in responsive evaluation and culturally relevant pedagogy, Hood (1998) argued that student learning is more effectively assessed through the use of assessment approaches that are culturally responsive. Combining the ideas of Ladson-Billings (1995) and Stake (1973), Hood (1998) promoted the development of “culturally responsive” performance-based assessments as a means of achieving equity for students of color. Hood (1998) noted that there were to be challenges and difficulties in the development of both performance tasks and scoring criteria that would be “responsive to cultural differences and adequately assess the content-related skills that are the focus of the assessment.”

“Culturally specific assessment” (Sul, 2019) represents an extension of Hood’s (1998) culturally responsive assessment onto a named worldview through the addition of an additional criterion: the assessment development process functions within a system of knowledge that exists within a named worldview. Thus, the formal definition of culturally specific assessment that will be utilized throughout this document is

- assessment that supports the academic development of students;

- is inclusive of a willingness to nurture and support cultural competence;

- aims to support the development of a sociopolitical or critical consciousness within students;

- is focused on constructs and measures of importance to educational practitioners and other key stakeholders; and

- functions within a system of knowledge that exists within a named worldview.